JIMMY BIVINS

Born: 6 December 1919 in Dry Branch, Georgia, USA.

Died: 4 July 2012 in Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Record: 112 fights, 86 wins (31 by KO/TKO), 25 Losses, 1 Draw.

Nickname: The Cleveland Spider-Man.

Division: Light-heavyweight and heavyweight.

Turned Pro: 15 January 1940.

Jimmy Bivins’ Career Breakdown

Had 20 fights in 1940, winning his first 19, including outpointing Charley Burley, before losing a majority decision against Anton Christofordis on December 2. He had beaten Christofordis three weeks earlier. In his next fight, in January 1941, Christofordis beat Melio Bettina to gain recognition as the National Boxing Association (NBA) light heavyweight champion.

Had an indifferent 1941, going 4-3 but scored a win over former NBA middleweight champion Teddy Yarosz.

1942 was a breakthrough year for Bivins as he beat former middleweight champion Billy Soose and reigning light-heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich in a non-title fight and also future champion Joey Maxim and title challengers Tami Mauriello and Lee Savold.

In 1943, Bivins won all nine of his fights, including wins over future heavyweight champion Ezzard Charles (voted greatest light-heavyweight of all time by Ring Magazine in 2002), Christofordis, Mauriello, Lloyd Marshall, and Melio Bettina. By the end of the year, having previously been rated No. 1 light heavyweight, Bivins was rated No. 1 heavyweight by Ring Magazine.

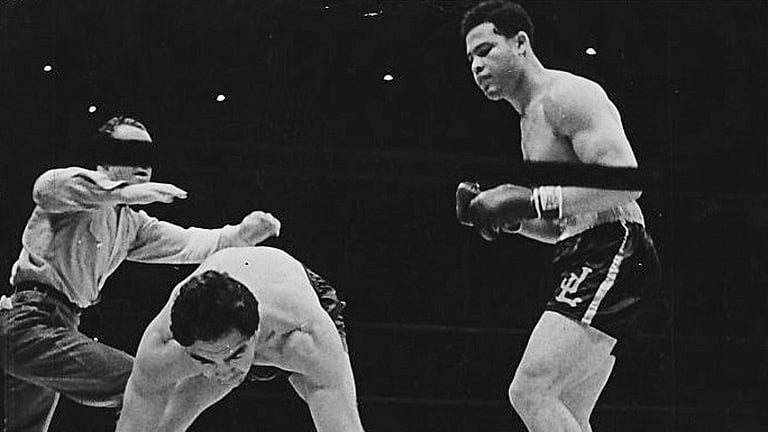

By 1944 the heavyweight title was effectively frozen during the Second World War with Joe Louis (below, right) and Bivins in the US Army, so Bivins did not get a title fight and had only one fight in 1944.

In 1945, Bivins had eight fights and was 7-0-1. He drew with Bettina in August, but he floored Archie Moore six times and knocked Moore out in the sixth round.

He had eight fights in 1946. He scored four wins in the first six weeks of the year but then suffered three losses in a row, dropping a split decision against future heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott—a loss that snapped Bivins’s unbeaten run of 27 fights—and being outpointed by Ezzard Charles.

In 1947 he was 8-3 in 11 fights, being beaten inside the distance by Charles and Moore.

1948 and he had nine fights, winning six, but was beaten on a majority decision by Moore, on points by Charles and on a split decision by Maxim.

1949 saw Jimmy busy as usual with eight fights, winning five, but was knocked out by Moore and lost a close decision to another future champion, Harold Johnson.

From 1950 to 1955 he stayed busy but was now losing more often. In 1951 he was beaten inside the distance again by Moore and, in August of that year finally fought the by-now ex-champion Louis but lost on points (some say this was an exhibition match, but it was over 10 rounds, and Louis was declared the winner).

Bivins was beaten in 1952 on points by Charles. In September 1952, he knocked out 18-1 prospect Coley Wallace who scored a win over Rocky Marciano in the amateurs and would play Joe Louis in the film “The Joe Louis Story”. Bivins retired in 1953 and made a brief return, winning two fights in 1955, beating future heavyweight contender Mike DeJohn in October and then retiring.

The Jimmy Bivins Fight Story

Bivins was a good track and field competitor but saw Jack Johnson fight in an exhibition which made him consider boxing. Although born in Georgia, from the age of three, Bivins lived in Cleveland and it was Olympic gold medallist Jesse (Cleveland) Owens who recommended he go for boxing instead of track and field as the pay was better! He won a silver medal at the 1949 National AAU championships and turned pro the following year.

He outgrew 154 lbs but did most of his fighting in the range of 175 to 190, at a time when anyone over 175 was classified as a heavyweight. This is why he was rated as No. 1 at both light-heavyweight and heavyweight at times in his career.

During his career, Jimmy faced seven future Hall Of Fame boxers and beat four, plus eleven fighters who held world titles, beating eight of them.

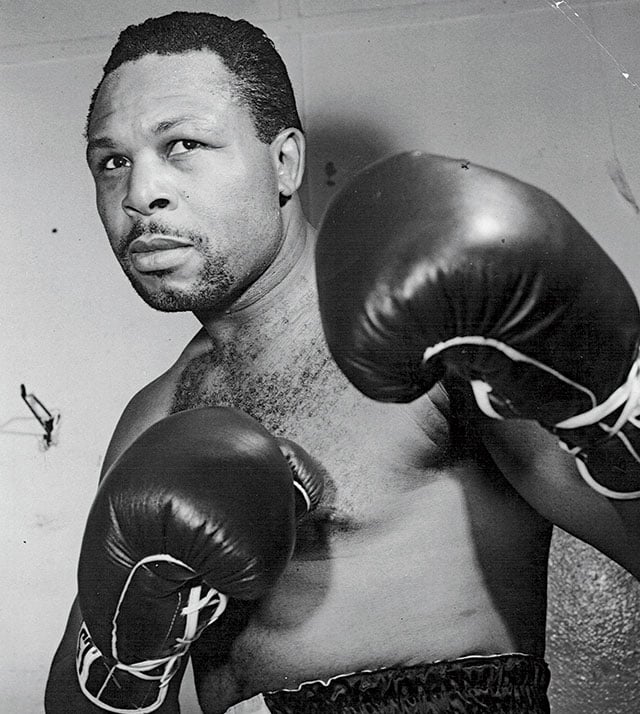

Between 1942 and 1946, he had a remarkable 27-bout unbeaten run during which he scored wins over Joey Maxim, Tami Mauriello, Bob Pastor, Lee Savold, Ezzard Charles, Anton Christoforidis, Lloyd Marshall, Melio Bettina, and other rated fighters and knocked out Archie Moore (pictured below).

It could be argued that if not for the Second World War, he would have fought Joe Louis for the heavyweight title with a chance of winning, but instead, he has had to settle for perhaps being the best heavyweight around that era to never receive a title shot.

Bivins’ Personal Background

Bivins was married three times. His second wife, Dollree Mapp, had her own claim to fame. She was around boxing and was arrested by police after a bombing at Don King’s (pictured below) home. Her arrest was not directly related to the bombing but the police searched her house and confiscated property and she won a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision relating to Search and Seizure.

On September 26, 2016, in Hempstead, New York, boxing promoter Don King was present at the Presidential Debate held at Hofstra University. This debate, the first of four for the 2016 Election, consisted of three Presidential debates and one Vice Presidential debate. NBC’s Lester Holt served as the moderator for this event. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

His third wife, Elizabeth, looked after Bivins well and he worked as a truck driver and helped advise young boxers at local gyms. The story took a turn for the worse when Elizabeth died in 1995 and he moved in with his daughter.

After a while neighbours became concerned at not having seen Bivins for a long time. The police entered his daughter’s house and found Bivins living in filth in the attic, seriously emaciated and mistreated.

His son-in-law was jailed for eight months and Bivins moved in with his sister before going to a care home, where he died from pneumonia in July 2012 at the age of 92.

He was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1994 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1999 and was inducted posthumously into the Californian Boxing Hall of Fame in 2015. The Cleveland Council also named a park after the man known as the “Cleveland Spider-Man”.