Similar to the sweet spot a boxer aims to find before launching an attack, the perfect perspective from which to observe and evaluate a sport like boxing lies in a delicate balance. This position is near enough to grasp the intricacies, yet not excessively close. It is distant enough to avoid confusion with hesitance, indifference, or trepidation.

In simpler terms, this can be described as a middle ground. It allows you to be near enough to seize any opportunity that arises, yet also maintain a safe distance to avoid stifling your own progress, getting blindsided by unexpected obstacles, or becoming overwhelmed by a difficult situation. From this vantage point, you have the opportunity to observe, analyze, identify vulnerabilities, and remain focused amidst the chaos.

And yet, due to both nerves and the emotion of it all, still there is a temptation to get close, too close, at which point nothing you land will be clean, substantial, or penetrating. This is as true for boxers as it is for writers. In fact, these days, with few capable of doing anything productive or worthwhile with their access, we find ourselves stuck in one enduring and frustrating clinch; told by the referee to “work your way out” only to just do the same work and expect different results.

Which is why reading a book like Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel – a self-confessed outsider – provides such a refreshing experience for anyone tired of hearing the same old words used to describe the same old situations. For in Headshot, her debut novel, Bullwinkel successfully creates a new kind of language for a sport whose lexicon is so familiar it has, like plenty of its participants, been used and abused until the point of exhaustion. Reading it, you are reminded immediately of the importance of outsiders. You are reminded, moreover, how the nature of boxing continues to provide a framework for the exploration of bigger, human issues, and how its language, though a tad trite, is still universal, accessible even to an outsider.

That is not to say Bullwinkel is a stranger to competition, mind you. An eight-time Junior Olympian in water polo, she has, although never boxed, clearly spent enough time around people trying to best her in ramshackle gyms and arenas to know all the tell-tale sounds and smells. She also consulted Ginny Fuchs, a female pro, to crosscheck specifics and ensure everything in Headshot rang true with Fuchs’ own experience of amateur boxing. In so doing Bullwinkel manages to create a captivating account of an amateur tournament involving eight teenage girls, told across two days. She structures the book as a series of face-offs, beginning at the quarter-final stage, and for the most part keeps the action in the ring, offering insight either via flashbacks, or flashforwards, or by describing, in vivid detail, the thought processes of the two girls who, in battling to advance, exchange more than just punches.

Unburdened by distance and the fictional nature of the story, Bullwinkel utilizes her eight boxers to offer profound insights that resonate with even the most fatigued boxing enthusiasts and writers. In her writing, she states that while Artemis Victor may lack an understanding of homeownership, she does comprehend the art of conquering opponents. Bullwinkel draws a parallel between owning property and defeating others, suggesting that acquiring a piece of land is akin to triumphing over fellow humans in a financial sense. This victory allows one to claim sole possession of the land, excluding others and solidifying their ownership through the accumulation of wealth.

“Headshot” is a novel that Rita Bullwinkel avidly reads from.

As the tournament progresses, Headshot inevitably waves goodbye to some of its characters. Yet, rather than just lose them entirely, Bullwinkel ingeniously decides that the victor in each round will carry with them a piece of their defeated opponent into the next. This is not done in any literal way, I should point out, but, as Bullwinkel explained during a reading at Daunt Books (Marylebone) on June 20, “I see them as cannibalising their opponent after beating them.”

Again, it is an interesting thought; perhaps one only an outsider, someone who endearingly refers to punches as “hits”, and who knows both nothing and everything about boxing, could make. Certainly, it cannot be argued that a boxer is changed by every man or woman they have trained to hurt in a ring. There is often a sense, too, that the relationship they form with these opponents is forever altered, typically for the better, as a result of them “communicating” inside this ring on fight night. Beforehand, they may have hated and denigrated each other, yet invariably a fight – for some, the only therapy they know – is the perfect environment in which to thrash it out, reach a greater understanding, and untether at the end of it either a better fighter or person – or, ideally, both.

In many ways, to call a novel like Headshot a “boxing book” is to not only undersell it but, to some extent, do it a disservice. It is, after all, much more – and better – than that. Indeed, by the time Bullwinkel, mid-fight, stops to reveal what her young boxers will end up doing with their lives into old age, you understand both the transience of a hobby/obsession and how boxing will constitute only a fragment of any person’s life, regardless of his or her level of interest, dedication, and prowess.

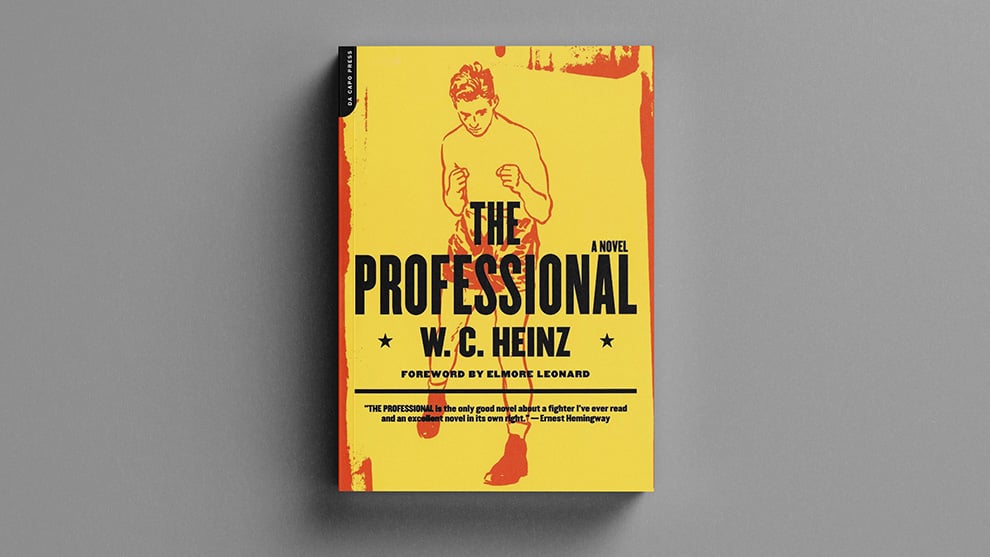

That, for me, was the most brilliant aspect of Headshot; the painting of boxing, so all-consuming and dangerous, as something that comes and goes and, once gone, never checks to see if you are okay. It is here Headshot finds a kinship with W.C. Heinz’s The Professional, another superb boxing-based novel which revels in its ability to hit parts of the body and soul others cannot reach. The two, published some 66 years apart, both beautifully capture a fundamental truth about boxing and its participants other so-called true stories, or nonfiction accounts, can’t even see, so restricted are they by either the perceived, convenient truth or the egos of the real-life characters involved. But in fiction, of course, there is always distance. And in this distance lies the truth.

The Professional by W.C. Heinz: An Unforgettable Classic.