By Oliver Fennell

THE script said the young, 6ft 7ins German with the cover star looks and the fashionably flowing locks would win the European title and then challenge Muhammad Ali for the world heavyweight championship in his home country.

“They forgot to tell me,” said the older, no-frills Yorkshireman with the craggy face and thick sideburns, and then he set about battering the 23-year-old to not only take the title but also his shot at the Greatest of All Time.

“Bernd August had the money men behind him,” says Richard Dunn, “but he had my fists in front of him.”

It had indeed all been set up for August to win. While the match was staged in London, he was the “home” fighter in every sense bar location. This was supposed to be his showcase; an advertisement to promote him as a challenger to Ali.

“Half the crowd were cheering him because he were a young, handsome lad,” recalls Dunn, 48 years later. “But to be quite truthful, I knew there were no way on God’s Earth he could beat me.”

Dunn’s reading of it proved more accurate than that of the money men, as he romped to a one-sided, third-round stoppage win. Yet it had been considered such a formality that August would beat Dunn that the date and location of Ali v August had already been announced: May 24, 1976, in Munich – just seven weeks later.

Yes, seven weeks to go from a European championship to a world title shot against the biggest star of them all. They were very different times – in a lot of ways.

The very next night, Dunn was interviewed by Harry Carpenter on BBC Sportsnight, having already been confirmed as taking August’s place against Ali.

Boxer A is supposed to fight for the title. Boxer B beats Boxer A, so Boxer B gets the shot instead. As simple as that. Imagine that. In today’s version of the sport, you can’t.

And in today’s interpretation of the sport, controversy and outrage are par for the course – expected, even. So, when watching today, it comes across as incredibly quaint, and as no better indication of how times have changed, when Carpenter’s interview with Dunn leads not with the announcement that one of Britain’s own has just been announced as challenger for the heavyweight championship of the world, against the most famous man on the face of the planet, but with the “controversy” that had followed the win that earned Dunn the chance of a lifetime.

“Bloody ridiculous; I didn’t like it at all,” said Dunn.

“I thought it was a damned disgrace,” said Dunn’s manager, George Biddles.

“It rather spoiled the occasion… it was all a bit cheap and nasty,” said Carpenter.

And what egregious offence was this?

Ali and his team had entered the ring post-fight, draped a gown over the victor’s shoulders and plonked a crown on his head. It was a good-natured way to anoint Ali’s next challenger, but one that didn’t sit well with this trio of traditionalists.

Nowadays, fighters want to wear crowns and dress like clowns, but Dunn’s days were simpler times, and Dunn was a simple man. And that is in no way meant as an insult. He’d probably take it as a compliment. “I were just a scruff from up north,” he says.

As such, he played the perfect straight-man as Ali inevitably hammed it up through the short build to their showdown. “You can’t take him on at trash talk, so you’ve just got to be the opposite,” says Dunn. “Though one time, after he finished talking, I said ‘every donkey likes to hear itself bray’. He got his guys to hold him back!

“The showbiz stuff got on my nerves, but I enjoyed Ali himself. He were a great fella; a fabulous man. When the cameras weren’t there, he were just an ordinary guy. I liked him.”

Dunn was already well known in the UK – as the top British heavyweights were at a time when their fights would be watched by millions on terrestrial TV – but became a full-on superstar by virtue of challenging Ali. The contrasts between him, a humble scaffolder from Bradford, and Ali, the most flamboyant personality the sport had ever seen, added to the storyline, and the fact he was such a massive underdog accentuated it.

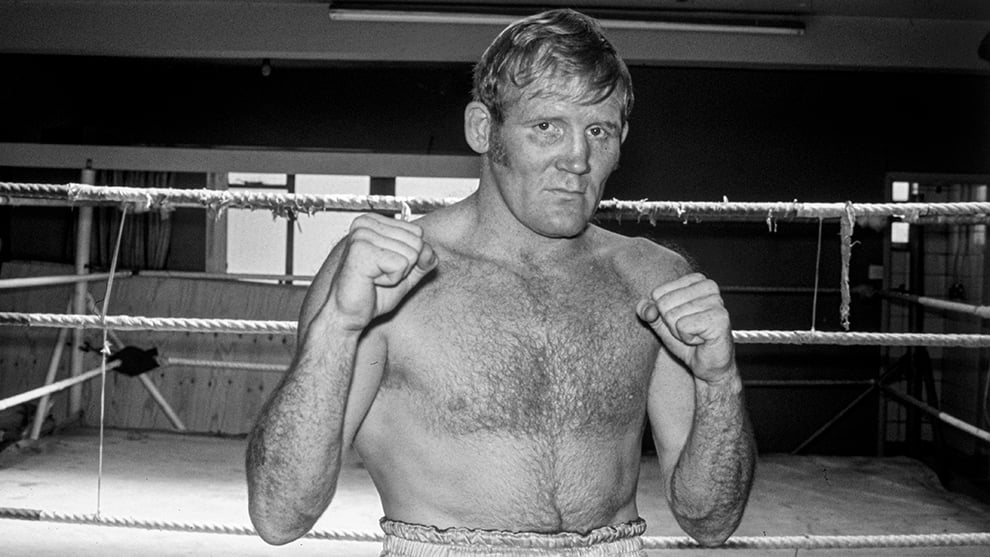

(Revised Caption) Richard Dunn undergoing training at Thurnston in Leicester.

“It were massive,” says Dunn. “I couldn’t walk on the street without people wishing me well. People were lining up outside restaurants as I ate, asking for autographs. But I don’t mind things like that. If they can be bothered to do that for me, I should be bothered to do it as well.

“I had some fabulous fans. But the media were a pain in the arse, to tell you the truth. They were turning up at my house; the phone never stopped. I couldn’t wipe my arse in peace. I’d hate to be a big star – you wouldn’t be able to fart, would you?”

Such distractions notwithstanding, Dunn set about preparing for this life-changing opportunity the only way he knew how: “I just trained the same as I did for everyone else, but longer and harder. I could do it all day. I were in the gym every day, up at half past four, just worked my arse off on that punchbag. I went running with people on my back. Old-fashioned, really old-fashioned training.

“I really did believe I could win. It only takes one punch. In my mind, I were looking at him on the floor. I had nothing in my head except beating him, no matter what it took. Gosh, I wanted to see him demolished. But he were such a great man. I adored him. I adored him from the beginning [of his career] and always wanted to fight him.”

In the great pre-Lennox Lewis tradition of British heavyweights, Dunn put forth a gallant but unsuccessful effort. The first two rounds were surprisingly competitive, with Dunn’s aggression and southpaw stance bothering Ali at times. But once the champion had solved the puzzle, it became a rout, with five knockdowns preceding a merciful fifth-round referee’s stoppage.

Dunn recalls the fight: “I just went out there and did my best. Tried to do my best, anyway – you’re talking about a man who were the best in the world, and still is. He were fabulous.

“A couple of times I did rattle him, and he told me that. But I got my arse kicked. You don’t think you’d enjoy getting your arse kicked, but I enjoyed every second of it – although I can’t remember anything after the second round!

“Looking at the video, though, you can see he doesn’t start his clowning ‘til the fourth round, once he felt comfortable. Until then, he knew he were in a fight and had to take it serious. Once he knew the score, what were happening, he started dancing about on those legs. I could have bloody chopped them off, Jesus!

“The picture everyone used afterwards, with me on the floor, they said it were a knockdown, but it weren’t – it’s just that I’d dropped half a crown and were trying to find it!”

This good humour, graciousness and humble self-assessment goes a long way towards explaining why Dunn captured the public’s imagination, and this popularity was even more evident after the fight than before it, when Bradford staged a homecoming parade for him, attended by thousands as he was driven through the streets in an open-top car, even though he’d lost.

Of course, being involved with Ali was the biggest factor in this fame, and that one fight continues to define Dunn, more so than the 44 others combined in what stands as one of Britain’s best heavyweight campaigns even without its flirtation with The Greatest. Does Dunn feel the Ali fight overshadows the rest of his career?

“Yeah, because sharing a ring with Ali makes people think you’re better than you are,” he says, again displaying that admirable self-deprecation.

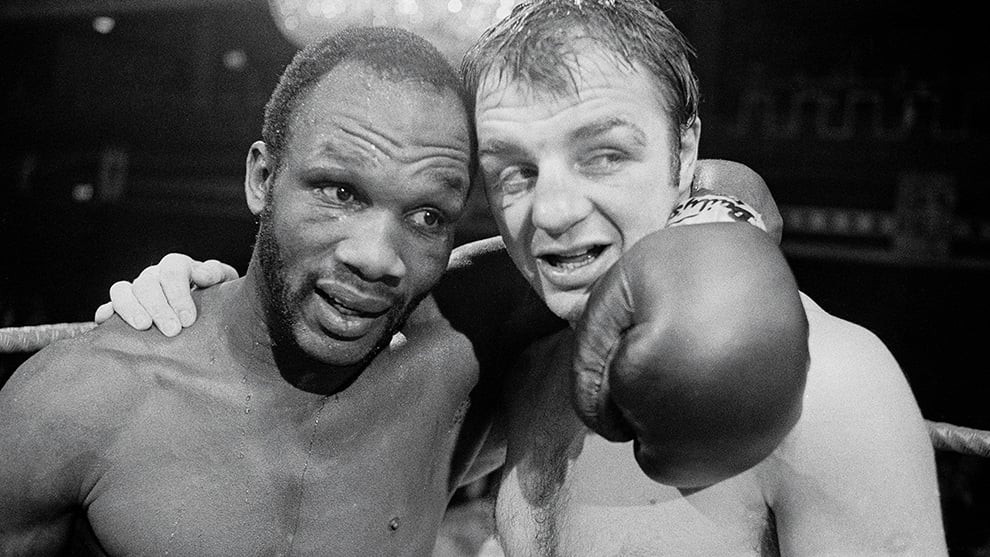

But make no mistake, Dunn was there on merit. Beating August for the European title had sealed the deal, but Dunn was also the reigning British and Commonwealth champion; titles he’d secured after a long career stuffed with some of the biggest domestic names of the time – Danny McAlinden (twice), Billy Aird (four times), Carl Gizzi, Neville Meade and Bunny Johnson (three times) – as well as a handful of world-rated contenders, such as Jimmy Young, Jose Urtain and Roy Williams.

In this photo captured on January 13, 1975, British heavyweight boxers Bunny Johnson and Danny McAlinden can be seen standing in the fighting ring. The snapshot was taken right after the match, in which Bunny Johnson emerged victorious and claimed the British and Commonwealth Heavyweight title. This remarkable achievement made Bunny Johnson the first black man to ever hold the prestigious title of British Heavyweight Champion. The picture was taken in London and is credited to Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

The second McAlinden fight and third Johnson encounter were for those titles and part of a six-fight winning run that led to August, and by extension Ali, and which saw Dunn rally from three consecutive defeats in 1974. Clawing his way back to contention led Carpenter to describe, prior to the August fight, how Dunn was a boxer who’d “come good late in life”.

He was all of 31 years old at the time. Again, a very different time.

These days, it really is true to suggest Dunn is of a fair vintage. He is 79, which makes him the oldest living British heavyweight champion.

Now living in Scarborough, Dunn was previously unaware – and thus pleased to learn – of this accolade, but tells of how he nearly fell a long way short of it, with an accident ending his working life 12 years after his boxing life had concluded.

Dunn had continued working as a scaffolder even as he fought at championship level, and had refocused on this full-time once he’d hung up his gloves. This work took him to an oil rig in the North Sea, off Aberdeen, in 1989. “We’d put scaffolding up on this rig and I went to check what the nightshift had done,” he says. “They hadn’t tightened it properly, so it collapsed as I were stood on it and I fell 40ft.

“It smashed both my legs to bits. The bones sticking out looked like scaffolding in my legs. They said I wouldn’t walk again. I said, ‘I’ll be up and about in no time, don’t you worry’. The look they gave me… Well, I were walking again nine months later. But I finished work because of that accident. If not for that, I’d still be working.”

If falling from a great height was what ended his working life, it was also, in a roundabout way, what got him started in boxing. Young Dunn was a sergeant in the Territorial Army’s 4th Batallion Parachute Regiment, and it was during his time in the forces that he was introduced to the sport.

“I did 40, maybe 50 jumps,” he says. “The first one were amazing, but I got a bollocking when I landed ‘cause I’d screamed on the way down!

“As for boxing, they put together a list of lads they wanted to fight for the Army team. I don’t know why they wanted me, other than I were built like a brick shithouse. But I didn’t mind – all I knew was that it [taking a boxing match] got me off work for a day.”

Prior to the army, Dunn had played rugby, and he resumed doing so after returning to civilian life. He was happy to do both boxing and rugby, but eventually had to choose. “The lads [at St Mary’s RFC in Halifax] all played hell with me, saying ‘you can’t fight; you’ve got a match tomorrow’. But I’d go and fight and win and then play the next day.

“I started getting more into the boxing game. I didn’t win any championships [as an amateur], not to my knowledge, but I fought internationally and you’d get prizes. I’d come home with a kettle or a twin tub. Altogether I had a hundred and something [amateur bouts] and I didn’t lose that many. I were built for it.”

And he’d already proved his aptitude with his fists long before he stepped in a ring: “I had a weird childhood. I were brought up in a children’s home in Leeds. I were just swooped up one day, ‘cause my mother had lots of children – I’ve been told it’s 11, but social services said 12 – and she didn’t feed them or clean them. As for my dad, no idea.

“But it were a fabulous place and I had some fabulous, lovely people looking after me. I weren’t a bad boy by no stretch of the imagination, but I weren’t the best up there [taps his head] and I had a very bad stutter. Ginger and a stutter, dear me… so I learnt to look after myself with my hands. If someone tried it on with me, I chinned them. I were cock of the school, put it that way.”

He would become cock of the boxing ring, too, once he focused on that sport and turned professional. Boxing also led to a settled family life, as he fell in love with Janet, the daughter of his trainer, Jimmie Devanney. “Now that’s a strong lass, my wife,” he says. “We never had any problems. I knew better than that, ‘cause she hit harder than anyone I faced in the ring!”

They married in 1966 and Dunn turned pro three years later as his family grew and therefore started costing him more. “I needed money,” he says. “I had two kids by that time [and would have three altogether] and I wanted to do the best for my family, so I went professional. I weren’t that clever with my boxing skills, but I were tough. Well, I thought I were until I got a few punches on the nose and thought ‘bloody hell, this is going to be a tough way to make a living!’.

“George [Biddles, manager] wanted me to move down to London, but I refused. I am a Yorkshire lad – always have been and always will be.”

And that “always” may be for some time yet. Dunn has already outlived every other man to hold the British heavyweight championship, but has at least one more goal to aim for.

“I want to live until I’m a hundred and a day,” he says.

“Only problem is, I need my kids to tell me how old I am!”