By Steve Bunce

IF the last moments of Deontay Wilder’s career took place in the Riyadh ring when he stumbled, turned and was hit flush by Zhilei Zhang, he would be in great company.

His last act in a boxing ring was to try and convince the referee, Kieran McCann, that he was fine; a second later he fell into McCann’s arms and at 1:51 of the fifth round it was the end for Wilder. He made a fortune in his career as the heavyweight champion of the world, he was in the neon glare at the end and not making peanuts in a shack on the edge of town.

A short history of the very last fights of heavyweight champions is depressing reading; there are tragic extremes, predictable failings and very few highlights. It is a shocking history of too many fat men with their fortunes gone, fighting novices for pennies in one of boxing’s many last-chance saloons. It is possible that nobody in sport falls further and harder than a world heavyweight champion. It would be a bleak game comparing the final fixture of faded stars across a dozen sports.

It is cruel to have a personal favourite, cruel to enjoy revisiting the sites and scenes of so many horrendous endgames. Joe Louis in 1951 against Rocky Marciano might just be the high for ugliness; it is, however, not the high for tragedy in the heavyweight division.

The Greg Page story is terrible. Page was a brilliant but flawed heavyweight like so many of the Lost Generation. In 2001, a long, long time after he was the WBA heavyweight champion, he drove to a place called Peel’s Palace in Erlanger, Kentucky. I know he drove, his partner for life, Patricia, told me the story. They had no money. Page was getting 1,000 dollars for fighting Dale Crowe for the vacant Kentucky heavyweight title.

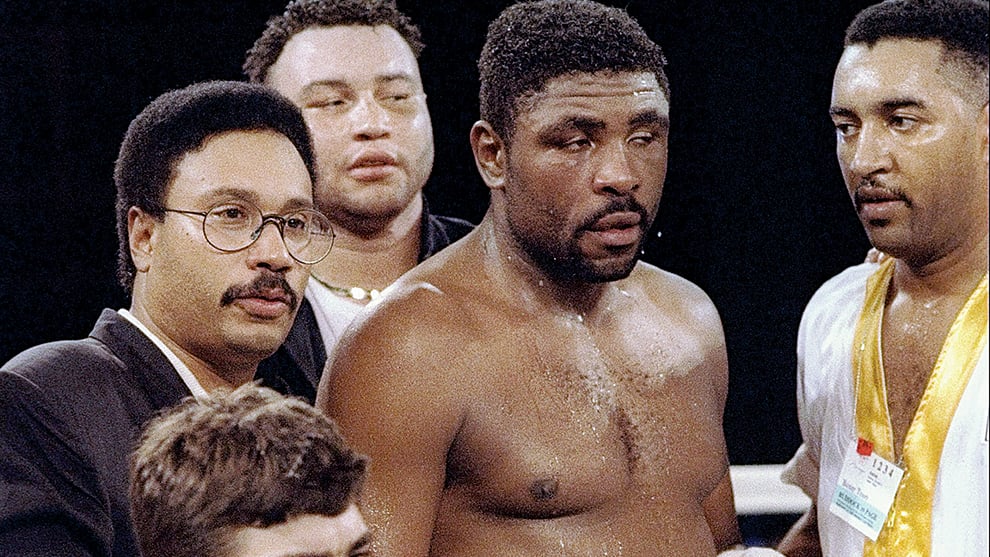

During a match against Donovan Ruddock, Greg Page observes the action from the sidelines. (Photo credit: Holly Stein/Allsport)

Page was knocked out in the last five seconds of the 10th and last round. He went down heavy; he was never getting up; the doctor ran from the ringside but not to the ring. He was gone, he left. Page was all alone; he survived but needed care after the operation to save his life. Patricia was his full-time care. She never left his side. One night in 2009, Page tumbled from his special bed and died when he was strangled by the same tubes that kept him alive. His last fight was unfair; Patricia found him in the morning. It was all over. She died two years later from a broken heart.

John Tate, another member of the Lost Generation, was also brilliant and deeply troubled by drugs and a hard life. He is one of the great lost and forgotten fighters. Tate won the WBA title in 1979 in front of 86,000 people in South Africa. It was a sanction-busting scrap; he lost the title the next year and went into freefall. His last fight was in 1988 and it took place on a March night at York Hall.

Tate lost over 10 rounds to Noel Quarless; it was close and hard and hard to watch. That was the end for Tate in legal boxing matches. He went deep the other way with prison, rehab, drugs and begging on the streets of Knoxville where he had once been a hero.

His life had gone bad years before the truck crash in 1998 that killed him. They found traces of cocaine in his blood. That is a bad exit for any champion at any weight; spend the two million dollars that you made, lose to Quarless at York Hall and then crash and die under the influence. His days in front of 86,000 were too distant to count.

It was a long, strange and violent journey for Mike Dokes from Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to Peel’s Palace, back in Erlanger. Dokes won the WBA heavyweight title at Caesars and 14 years later was knocked out in the second round of his final fight at Peel’s Palace in 1997. The million-dollar paydays were long gone for Dokes, but the fall was so predictable. The men from the endless chaos of the Lost Generation seldom disappoint. Dokes went on to have violence and prison rule his life until his death in 2012.

Mike Tyson finished the boys from the Lost Generation in the ring in fight after fight, and his descent and final fight was equally disturbing and predictable. Tyson’s end against Kevin McBride in 2005 was more like a sacrifice. The last fight for Larry Holmes was dignified by comparison; Holmes, in his 75th fight, beat Butterbean on points over 10 rounds in 2002.

Holmes had won the WBC heavyweight title in a 15-round classic at Caesars Palace in 1979. The man from the Norton fight was fighting only on memory when he beat Butterbean – I have never been brave enough to watch it, but I’m guessing that Larry never moved much.

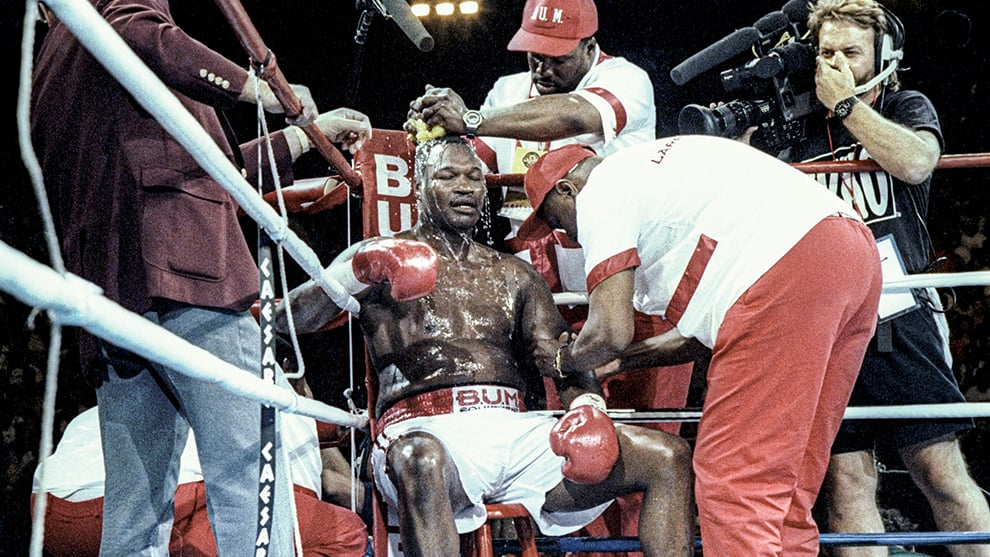

On June 19, 1992, in Las Vegas, Nevada, Larry Holmes finds himself in his corner during the breaks between rounds in his match against Evander Holyfield. After 12 rounds, Holyfield secures victory with an unanimous decision. Photographic credit: Holly Stein /Allsport

The Holmes exit was not bad compared to Page or Tate, and there have been decent last fights, both wins and losses by heavyweight champions at the end of their careers. Few, however, go out on their terms and with their faces unmarked and their pockets packed with cash. There always seems to be a lack of dignity and respect in the last fights of the heavyweight champions. Lennox Lewis walked with his head high, a rare fighting man.

Wilder might just have walked away with his health, his looks, his wealth and his legacy intact. In the real world, he has some other problems. Hopefully, those problems will have nothing to do with him fighting on.